On the restoration of the Bourbons, MacDonald was met favorably by Louis XVIII. He rode next to the King’s carriage as the royal family returned to Paris. The crowds lined the streets as MacDonald and the royal procession made its way down Rue Saint-Honoré and towards the Tuileries Palace. The royal family had not seen the palace since the battle and massacre of the King’s Swiss guard that took place there in 1792 . Napoleon’s Old Guard had been forced marched from Fontainbleu to Paris to meet the king, despite being encouraged to acknowledge the soldiers and to support reconciliation, Louis XVIII snubbed the Old Guard, causing much resentment and sowing the seeds of Napoleon’s rebellion against the King 10 months later. Louis XVIII subsequently elevated MacDonald to his Council of War, which had been given the task of reorganising the French forces and advising the King on military matters. The council only met twice and Louis never summoned it again. MacDonald considered this a serious mistake as it was clear that the King had rejected the opportunity to bring together experienced voices in preference of returning to the old ways of favoritism, particularly for the nobles. In MacDonald’s own words, “decorations and promotions were being lavished on the incapable and careless, while merit languished and vegetated in subordinate ranks.”

The French political system was also reorganised and MacDonald became a peer and member of the Upper Chamber, voting consistently as a moderate-liberal.

One such bill drafted by the King related to freedom of the press. MacDonald believed that the bill did not sufficiently protect freedom of the press and was in violation of the new Charter. He subsequently voted against the legislation but the bill passed by a single vote. One of MacDonald’s roles at this time was to inform the King of any Bills that had recently passed. The King met with MacDonald and spoke to him in a severe tone, MacDonald noted that the Kings eyes were fixed on “him like a lynx”. The King haughtily told MacDonald that when he goes to the trouble of drafting a Bill he had good reasons for wishing it to pass, expressing surprise that MacDonald voted against him. MacDonald rebuked the King by saying,

“Sire, your Majesty did not take me into confidence with regard to your Bills. They ought all to pass if they are drawn up by your Majesty. If the initiative is to belong to your Majesty alone, they might as well simply be registered, and we might remain dumb like the former Legislative Body. If, however, I have correctly understood the intentions of the Charter, it gives to every individual freedom of opinion and vote. I fancied that in this Bill I discovered a violation of Article 8, and I employed that liberty conscientiously, as I shall always do.”

The dumbstruck King did not respond, bowed and left the room. MacDonald was to have mixed relations with Louis XVIII, just as he had previously with Napoleon. The King eventually became sufficiently comfortable with MacDonald’s bluntness to jokingly address him as ‘His Outspokenness’.

Louis XVIII’s rule became increasingly unpopular and his neglect of the army caused resentment amongst the soldiers. When Napoleon escaped from exile and returned to France in 1815, many regiments rallied to the Emperor’s side. MacDonald opposed Napoleon’s return fearing the possibility of a protracted civil war and yet another war with the European powers. Although MacDonald was largely sympathetic to the disillusionment that the soldiers felt against Louis XVIII, he felt it was important that they continued to undertake their duties. He was also unsure that his soldiers would follow him in fighting against Napoleon and he rode to speak to them to secure their loyalty. Forming his men into a square, MacDonald gave an impassioned speech praising their conduct and warning of another imminent war should Napoleon return to power. He then asked the men to join with him in crying ‘Long Live the King!’ but was met with a stony silence. Suitably alarmed, he left and tried this same routine on a number of other units, but again was met with silence. Even when joined by the Duke of Orleans (the future King Louis-Philippe I) the men would not budge and MacDonald recalls the Duke being “crimson with anger” as the men refused to proclaim loyalty to the royal family even when being directly addressed by name.

MacDonald watched his regiments join Napoleon’s forces as they approached Lyon. As he tried to escape, a drunk Brigadier attempted to capture MacDonald. Scarcely were the words to surrender out of the Brigadiers mouth when MacDonald floored him with a single punch. MacDonald disguised himself and escaped with General Digeon, whose troops had also deserted to join Napoleon.

On returning to Paris, MacDonald met with the King, who was delighted that MacDonald had remained loyal. The King offered MacDonald a reward, which was refused as MacDonald would not accept any reward simply for doing his duty. MacDonald appears to have been the first person to inform the King that the situation was hopeless and that he should abandon the capital. This caused Louis XVIII great alarm and he dismissed MacDonald, claiming instead that he would speak to his ministers about the best course of action. MacDonald recollects that the ministers were in fact so panic stricken that they were incapable of giving the King any sensible advice.

At a council of war MacDonald spoke bluntly about the inadequate measures being put forward to protect the King. A heated argument ensued with the Duke of Berry (The future King Charles X) and MacDonald later offered his resignation. When news reached Paris that Marshal Ney and his soldiers had defected to Napoleon, the Duke of Berry told MacDonald that he would now be in charge of all of the King’s forces. Realising that resistance was now futile, he escorted the King out of Paris. During the escape Louis became particularly distressed that his favourite pair of slippers had been stolen. MacDonald quietly wondered to himself why the King had not shown similar interest in his Kingdom.

As Napoleon retook Paris, MacDonald led Louis XVIII to British forces on the continent. The King was touched by the loyalty shown by MacDonald and offered him a diamond encrusted snuff box and an emotional farewell. MacDonald understood the military situation and assured the King that he would see him back in Paris soon. When MacDonald returned to the capital he received news from a messenger that Napoleon would welcome a meeting with MacDonald and thanked him again for everything that he had done to help him in the past. MacDonald was sympathetic to Napoleon but refused, saying that Napoleon would understand that he had made an oath and would not break it, just as he had done in service of the Emperor. He also feared the terrible retribution of the foreign powers, who would undoubtedly win the war that was to come. Shortly afterwards the news arrived that Napoleon had been defeated at the Battle of Waterloo.

MacDonald was again by the Kings side as he was restored to the throne for a second time. MacDonald noted that the Parisians seemed much less enthusiastic than they had been for the first restoration. Like all of those who remained loyal to the Bourbons, MacDonald was offered numerous promotions, some of which he refused. He eventually became a minister in the French Government, accepted the role of Major-General of the King’s Guard, and was elevated to Commander of the Army of the Loire. MacDonald also helped some of the officers who had been proscribed by the Bourbons to escape from France.

In 1825 MacDonald left France for a tour of Scotland, the highpoint of which was the visit to his father’s birthplace on South Uist and meeting many of his extended family. His tour of Scotland was extensive and took him from the borders to the islands, but he rarely stayed in any location longer than a single day. His tour also briefly brought him to Ireland and England.

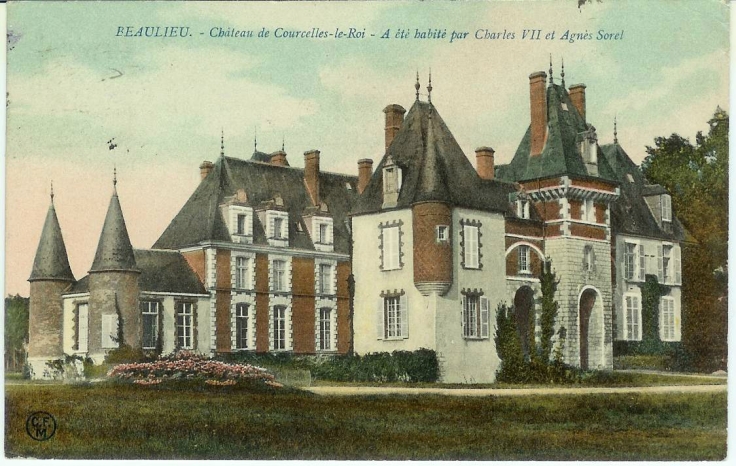

On returning to France, MacDonald remained in politics until the July Revolution of 1830 when Charles X abdicated in favour of Louis-Phillippe I. MacDonald chose this moment to bow out of politics, retiring to the Chateau of Courcelles le-Roi where he died in 1840. He is buried in division 37 of Cimetière du Père Lachaise in Paris.

Marshal MacDonald’s only son, Alexander Louis-Marie MacDonald inherited his father’s title and became the 2nd Duke of Taranto. He was a prominent French politician in his own right and became Chamberlain to Emperor Napoleon III. He was subsequently inducted into the Legion of Honour for his services to France.

The Marshal’s grandson, Napoleon Eugène Alexander Fergus MacDonald was the 3rd and last Duke of Taranto. He died in poverty in 1912 and was buried in a mass grave at Bagnolet, near Paris.

Marshal MacDonald of France had an extraordinary career and rose to become one of the highest ranked French military commanders of the Napoleonic Wars. He was present at some of the most important battles in European history such as Valmy and Wagram. MacDonald was also a survivor, managing to endure the military disasters that took place during the retreat from Moscow and the Battle of Leipzig. Known for his outspokenness, he still managed to gain the respect of often opposing factions, maintaining friendly relations with Emperor Napoleon, King Louis XVIII and Tsar Alexander I, who all trusted MacDonald and sought his services. His extensive military service for the various incarnations of the French Government, whether that be Bourbon, Republican or Napoleonic, is testament to his professionalism as a soldier and the seriousness he placed in the oath he gave to faithfully serve the political realities of his time. His political career is often over shadowed by the events that took place in his military career. Indeed it’s worth remembering that MacDonald’s actions helped elevate Napoleon to power during the coup of the 18 Brumaire, but also to ensure Napoleon’s surrender to allied forces in 1814 to prevent needless bloodshed. By the end of his career, he had not only risen to the top of the French military, becoming an army commander, he had also been a senior advisor to the King and a prominent member of the French legislature.

He is remembered amongst Napoleonic historians as a solid and dependable commander, rather than a brilliant one. Most historians rank MacDonald amongst the middle tier of Napoleon’s Marshals, although the Emperor himself certainty trusted MacDonald’s abilities enough to allocate large formations to his command. Yet despite his glittering success one of the greatest tragedies of MacDonald’s life is that he remains largely an unknown figure in his ancestral homeland of Scotland.

–

Dá Dhómhnallach

Somhairle MacGill-Eain‘Na do ghaisgeach mór láidir;

‘Nad churaidh miosg nan curaidhean,

Dhùin thu geata Hougomont.

Dhùin thu ‘n geata ‘s air a chùlaibh

Rinn do bhráthair an spùilleadh.

Thog e tuath an Gleann Garadh –

Am beagan a bh’air fhágail dhiubh –

Is thog e tuath mu Cheann Loch Nibheis

Is thog e tuath an Cnóideart.

Cha b’fhearr e na Fear Dhùn-Bheagain:

Rinn e milleadh air Cloinn Domhnaill.De rinn thusa ‘n uair sin,

A churaidh mhóir láidir?

Fiach na dhùin thu aon gheata

An aodann do ghalla bráthair?Bha ann ri d’linn-sa fear eile,

Curaidh eile de Chloinn Dhómhnaill,

Curaidh Bhágram, Leipsich, Hanau.

Cha chuala mi gun do thog esan

Aon teaghlach mun Mheuse

No mu abhainn eile.

Cha d’rinn esan milleadh

Air Frangaich no air Dómhnallaich.Nach bochd nach táinig esan

Le Bonaparte a nall.

Cha thogadh esan tuath

Air sgáth nan caorach óraidh,

‘S cha mhó chuireadh esan gaiseadh

Ann an gaisge mhóir Chloinn Dómhnaill.

Nach bochd nach rodh esan

‘Na dhiuc air tir an Eórna

Is ‘na phrionns air Albainn.Nach bochd nach táinig esan

Le Bonaparte a nall

Fichead bliadhna mun táinig,

Cha b’ann a dh’èisteachd sodail

O’n t-sliomaire sin Bhátar

No a chruinneachadh na h-ùrach

As an t-seann láraich,

Ach a chur an spionnaidh ùrair

Ann am fuidheall a cháirdean.Nach bochd nach táinig esan

Gu cobhair air a cháirdean.–

The Two MacDonalds

Sorley MacLeanYou big strong warrior,

you hero among heroes,

you shut the gate of Hougomont.

You shut the gate and behind it

your brother did the spoiling.

He cleared tenants in Glengarry –

the few of them left –

and he cleared tenants about Kinloch Nevis,

and he cleared tenants in Knoydart.

He was no better than the laird of Dunvegan.

He spoiled Clan Donald.What did you do then,

you big strong hero?

I bet you shut no gate

in the face of your bitch of a brother.There was in your time

another hero of Clan Donald,

the hero of Wagram, Leipsig, Hanau.

I have not heard that he cleared

one family by the Meuse

or by any other river,

that he did any spoiling

of French or of MacDonalds.What a pity that he did not come

over with Bonaparte!

He would not clear tenants

for the sake of the gilded sheep,

nor would he put a disease

in the great valour of Clan Donald.

What a pity that he was not

Duke of the Land of the Barley

And Prince of Caledonia!What a pity that he did not come

over with Bonaparte

twenty years before he did,

not to listen to flannel

from the creeper Walter

nor to gather dust

from the old ruin

but to put the new vigour

in the remnant of his kinsmen!What a pity that he did not come

to succour his kinsmen!–

Hi Colin

That’s a great article. By chance I’m also writing an article on Scots in France. Would it be alright if I quoted your article, and what’s the correct way to do it? So that I don’t look like a plagarist! 🙂

Keith MacDonald

Hi Keith! I will send you an email.

Thanks, I look forward to that.

Hi Keith, I emailed you on your gmail account, let me know if you have any problems.