The American Civil War is not a conflict that figures prominently in the consciousness of Europeans. Few people in Scotland would be able to tell you much about the major figures of the war, why it happened or what the defining events of it were. Given Scotland’s long established connections to North America, this should actually come as a surprise. Scots played a prominent role in the war, for both sides, and the ‘War Between the States’ greatly affected the economic and political conditions that were prevalent in Scotland during the 1860s and beyond.

Our current ignorance is in stark contrast to the Scots of the time, who were well informed and who often had sophisticated understandings of the arguments on both sides of the conflict. Indeed, abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass had visited Scotland as early as 1846 and given the reliance of the Scottish cotton industry on cotton from the American South, it is hardly surprising that Scots viewed these events as something directly relevant to them, and not as an abstract foreign dispute.

It is said that while history doesn’t repeat itself, it certainly rhymes. As Scotland grapples with its own understanding of its future, whether that be independence or union, the Scots of the mid-19th century were similarly divided on the issue of independence or union for the American South.

So for the benefit of the people on both sides of the Atlantic, here is a look at some of the more interesting connections that existed between Scotland and the Confederate States of America.

William Watson and the SS Rob Roy

William Watson was born in Skelmorlie, North Ayrshire in 1826. He was the son of an Englishman, Henry Watson who had moved to Skelmorlie to work as a landscape gardener at the Ash Craig estate. Henry remained the gardener of Ash Craig for 40 years, building a cottage named Halketburn, where he raised his 8 children. Not content to follow in his father’s footsteps, William Watson emigrated from Scotland to Bermuda in 1845 before moving to Louisiana around 1850. Although opposed to secession he enlisted with the Confederate Army for a one year term because he felt his personal honor, and that of Scotland, would be at risk if he did not follow the army. He fought at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek but refused to accept a commission as an officer as it would require him to renounce his allegiance to Queen Victoria.

Watson was discharged in 1862 and he soon discovered that the entire business district of Baton Rouge, including all of his property, had been destroyed by Union forces to provide clear fields of fire for their gunboats. When he returned to his old regiment, the 3rd Louisiana Infantry, he became caught up in the Second Battle of Corinth, where he was wounded and captured as the Confederates retreated. With the assistance of a Scottish member of General Rosecran’s staff, Watson was paroled by the US Army and upon returning to the Confederate Army, he was discharged due to injury. Watson then hired a ship, which he named the SS Rob Roy, and became a blockade runner, ferrying much needed supplies into Texas. He returned to Scotland in 1865 and when he married Helen Milligan in 1871, his address was given as 127 Argyle Street, Glasgow. He wrote two books, ‘Life in the Confederate Army’, published in 1887 and ‘The Adventures of a Blockade Runner’, published in 1892. He died at Beechgrove House, Skelmorlie in 1906.

The Clyde Shipyards

The shipbuilders of the Clyde were largely sympathetic to the Confederate cause during the Civil War. As the Confederacy was strangled by the Union blockade, the Clyde shipyards were commissioned to build ‘blockade runners’. These transports were built lightly to outrun Federal ships and bring desperately needed supplies to Confederate cities. Although Britain was technically neutral in the conflict, the government did not intervene as long as the correct paperwork was provided for the construction of the ship.

By 1864, a total of 27 shipyards and 25,000 men on the Clyde were working around the clock to build ships for the Confederacy. Around 3,000 Scots worked on-board these ships in direct violation of British neutrality in the conflict. Around a third of all Confederate Blockade runners were built at Scottish shipyards situated all along the Clyde from Govan to Greenock. Such examples include the CSS Robert E Lee and SS Fingal, which were constructed in Glasgow, in addition to the Greenock built SS Tristram Shandy and CSS Advance. Recent research suggests that Confederate agents were based in Bridge of Allan in Stirlingshire, where they could avoid Yankee counter agents and meet with shipping magnates. A furious US Government later called for compensation from the British Government for prolonging the Confederate war effort, maintaining that British shipyards could be liable for a staggering £8 billion in damages. After the US Government threatened to seize Canada and the West Indies as compensation, Britain eventually agreed to pay a mere £7.4 million in 1877.

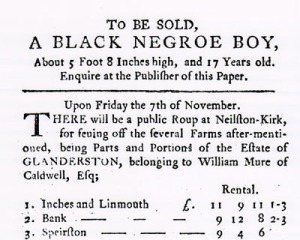

King Cotton

In 1860 Southern plantations supplied 75% of the world’s cotton and the highly industrialised cotton industries of Scotland were almost entirely reliant on the cotton imported from the Southern states. The Southerners used the slogan ‘King Cotton’ to refer to the economic strength of the resource and the perceived political leverage that it gave over cotton dependent economies such as those in Britain and France. The importance of cotton to the Scottish economy is demonstrated in the 1851 census, which shows almost a tenth of Glasgow’s 370,000 people engaged in some form of employment connected with cotton manufacturing.

The Confederates believed that if they could starve the European nations of cotton and damage their economies, Britain and France would be compelled to recognise Southern Independence. As the union blockaded Southern ports, cotton imports dried up in Europe, marking a period of ‘cotton famine’ in Scotland. As reserve stocks dwindled, the cotton industry in Scotland faced an immediate crisis which led to a rapid decrease in production and mass unemployment. The American Civil War caused irreversible economic damage that led to the permanent decline of the cotton industry in Scotland. It also changed Scotland’s economic priorities away from the cotton trade, just as cotton had been a diversification from the tobacco trade. Yet some 150 years later there seems to be little recognition that many industrialists in the West of Scotland made considerable profits as a direct result of slavery in the American South.

Scottish Soldiers

The Confederacy had no shortage of soldiers who were either Scottish or had Scottish ancestry. This is reflected in the number of Scottish ‘Regiments’ that were formed by volunteers determined to rally their men around a distinctive ethnic or cultural background. In reality these ‘regiments’ were usually company strength and were amalgamated into regiments when the Confederate Army increasingly standardised it’s units as the war progressed. Some of these Scottish units included the ‘Scotch Guards’ from Alabama, the ‘Scotch Tigers’ of North Carolina and the ‘Montgomery Highlanders’ of Virginia. There are many notable individual examples of Scottish soldiers serving in Confederate forces, including Lt-Colonel Peter J Sinclair of the 5th North Carolina Volunteers, who was born on Tiree in 1834 and the Edinburgh born Colonel Robert Alexander Smith of the 10th Mississippi Infantry, who was also the personal bodyguard of President Jefferson Davis.

The Civil War caused not only political divisions, but conflict within families. Two Scottish born brothers, James and Alexander Campbell, became a personification of that division. Emigrating to America in the 1850s, James Campbell eventually settled in South Carolina, while Alexander Campbell settled in New York. James ultimately became a member of the Charleston Battalion, while Alexander was a member of the Union 79th New York Highlanders. They faced each other at the Battle of Secessionville and James Campbell later defended Fort Wagner against the 54th Massachusetts, as depicted in the 1989 film, Glory.

Kate Cumming

Kate Cumming was born in Edinburgh between 1828 and 1835. In the 1840’s, her family emigrated to Canada and then Alabama. Her mother and two sisters left for England at the beginning of the war in 1861 but Kate stayed in Alabama as her father and brother enlisted in the Confederate Army. She was later inspired to help the Southern cause by becoming a volunteer nurse. Together with 40 other women she joined the Confederate Army in Corinth, Mississippi to help nurse some of the 23,000 Confederate and Union soldiers who were wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.

Kate Cumming was born in Edinburgh between 1828 and 1835. In the 1840’s, her family emigrated to Canada and then Alabama. Her mother and two sisters left for England at the beginning of the war in 1861 but Kate stayed in Alabama as her father and brother enlisted in the Confederate Army. She was later inspired to help the Southern cause by becoming a volunteer nurse. Together with 40 other women she joined the Confederate Army in Corinth, Mississippi to help nurse some of the 23,000 Confederate and Union soldiers who were wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.

While many considered female nursing inappropriate for a women of Cumming’s social class, she was of the firm belief that every patriotic Southern woman should help the cause. The work undertaken by female nurses like Cummings led to the re-organisation of Confederate field hospitals and a reduction in the death rates amongst wounded soldiers. Following the end of the war she became a staunch proponent of the Lost Cause ideology and her diaries are considered an important source of information on Civil War nursing. An active member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, she died in 1909.

Rednecks

It is well known that the derogatory term of ‘redneck’ has long been used to belittle and demonise the people of the Southern States. What is less known however is that the term itself originated in Scotland as an insult against radical Presbyterians. In the late 1630s, Scottish Covenanters vehemently opposed the imposition of the Church of England on Scotland and to demonstrate their commitment to the new Presbyterian religion they often signed their manifestos with their own blood. Some of the Covenanters who rebelled against Charles I wore a red cloth around their neck as a mark of identity, this was seized upon by the Scottish ruling elite who then used the pejorative term of ‘red neck’ to describe radical Presbyterians.

The earliest known use of the term in the United States dates from 1830 and was used to describe Presbyterians of Fayetteville, North Carolina. While the origins of the modern understanding of ‘redneck’ are disputed, it is more likely that it originates from a description of poor farmers, who had sun burnt red necks from working long hours in the field. A similar term of ‘red legs’ exists in West Indian vernacular to describe white slaves whose ancestors had been sent to the Caribbean by Oliver Cromwell.

Sir Walter Scott

Through James MacPherson’s historical epic Ossian and Robert Burn’s poetry, Scottish literature of the early 19th century had already established itself as influential in an international context. In the American South, the works of Sir Walter Scott and other expressions of romanticised Scottish culture had become very popular and enormously influential on Southern views towards chivalry, honor and romantic nationalism. Scott’s tales of Jacobites and medieval knights resonated with Americans and between 1814 and 1823, more than a million copies of his novels and poems were sold in the United States. Mark Twain was the most vocal critic of the influence of Scott, claiming that “Sir Walter had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he is in great measure responsible for the war.” Lachlan Munro argues that the development of the idea of a ‘Southern Aristocracy’ as it existed in the pre-war period was a result of Scott’s enormous influence on the upper class planters of the deep South.

As tensions developed between the North and South in the 1850s, Scott’s literature provided many appealing analogies for Southerners. Scott depicted Scotland as a small yet noble nation, an underdog determined to protect its heritage and identity in the face of a hostile larger neighbour. The parallels between this view of Scotland and the Confederacy were unmistakable for Southerners and figures such as Robert E Lee fit comfortably into that thinking as an Arthurian figure and a chivalric knight. The morale of the South was sustained by these concepts, which gave the Confederacy a historical pedigree to the warrior society of the romanticised Scottish Highlands. Even in defeat Scott’s influence on Southern thinking was unshakable, Lost Cause ideology developed as the most modern incarnation of the forlorn Jacobite cause – noble, heroic and ultimately untainted by defeat.

Jefferson Davis

President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, was himself primarily of Welsh heritage, his ancestors having emigrated from Snowdonia in Wales. However, like many other prominent figures of the Civil War era he visited Scotland as part of a European tour, visiting three times between the late 1860s and early 1870s. On one of these trips Davis met with James Smith at his home of Benvue House in Glasgow. Smith had become acquainted with Davis when he emigrated from Scotland and founded an iron works in Mississippi. James Smith’s younger brother Robert had also been a bodyguard to Davis and was killed at the Battle of Munfordville.

Through letters and diary extracts, we have a good idea of where Jefferson Davis traveled when he visited Europe and it is clear that Davis and the Confederacy had considerable support in Scotland. On one such trip he left the Broomielaw in Glasgow, where a large group of people had assembled to cheer for him. Upon reaching Greenock he was greeted in a similar manner. Davis also wrote that he was aware that a “very large proportion of the inhabitants of Edinburgh appreciate and sympathise” with the Southern people in their “struggle for freedom and self government”. On travelling north, he visited Oban, Mull, Fingal’s Cave, Inverness and the Culloden Battlefield. He was given a tour of the battlefield by the editor of the Inverness Courier, Robert Curruthers. When walking the field, they met a local shepherd and Mr Curruthers asked if he was impressed to be in the presence of Jefferson Davis and if he had ever heard of the Southern Confederacy. The confused shepherd replied that he had never heard of the Southern Confederacy and asked if it was some kind of company in England. Jefferson Davis took it in good humor and whispered to Robert Curruthers that his shepherd friend “obviously does not read the Inverness Courier.”

The Rebel Yell

The blood curling Rebel Yell was the distinctive battle cry of the Confederate soldier during the Civil War. No contemporary recordings of the yell exist, and debate continues about how exactly it sounded and the nature of its origins. Historian Shelby Foote described it as “a foxhunt yip mixed up with sort of a banshee squall” while a Union soldier said that “if you claim you heard it and weren’t scared that means you never heard it”. The closest we will ever get to it is a fascinating recording released by the Smithsonian Museum which shows 90 year old Confederate Veterans doing the Rebel Yell at a Civil War reunion of the 1930s (view here).

One theory put forward by the historian Grady McWhiney suggests that the Rebel Yell was in fact the battle cry of the Scottish Highlanders, transplanted to America and passed down the generations by Scottish emigres. On the surface this theory seems plausible, and there are undeniable similarities between the Rebel Yell and the distinctive howl and whooping battle cry that Scottish Highlanders were known to have used during battles such as Killiecrankie. However while it makes for an interesting anecdote, it probably doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It is much more likely that the Rebel Yell originates from Native American war crys, possibly heard by soldiers that fought the Native Americans in the series of wars that took place before the Civil War. Indeed William Howard Russell, war correspondent for The Times noted that the yell had “a touch of the Indian war-whoop in it”. So while there might not be a shared origin for the Scottish and Confederate war cry, there is an undeniable similarity in their descriptions – eerie, haunting, high pitched and very effective at unnerving the enemy.

Useful Sources

William Watson-

American Civil War Scots – William Watson

Dead Confederates – A Civil War Era Blog

Clyde shipyards-

The Herald Scotland – How the Clyde Boomed from a Confederacy of Civil War Greed

The Scotsman – Scots and the American Civil War

Wessex Archaeology Online – The PS Iona

The Independent – Bridge of Allan, the Home of Confederate Agents in Scotland

Kate Cumming-

Encyclopedia of Alabama – Kate Cumming

King Cotton-

Electric Scotland – The Industries of Scotland

Glasgow Punter Blog – Glasgow and the Slave Trade

Scottish Soldiers-

American Civil War Scots – Biographies

Sue Sinclair’s Genealogy – Lt Col Peter Sinclair

Teaching American History in South Carolina- Letters between James and Alexander Campbell

The Civil War Trust – Brother Against Brother

Walter Scott-

The Herald Scotland – Scotland and Lincoln

The New York Times – Author of the Civil War

Lachlan Munro – Sir Walter Scott and the Civil War

Jefferson Davis-

Fantastic and so informative. Liked the wee piece on the a Rebel a yell!

Very interesting.

So, Scotland was a big fan of slavery?

Hi Patrick,

I believe Frederick Douglas already answered that for you when he said,

“I have never seen a people more deeply moved than were the people of Scotland on this very question.”

Being Scottish this sent pride coursing through my veins!! Brilliant read! People died and that is always bad and sad. When Scottish people say “Scotland developed the modern World” we get a strange look or saying back. But it’s true… https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_the_Scots_Invented_the_Modern_World

Great read

Scots, Scotch-Irish, and Ulster Scots are credited with many of the modern invention that make Western Civilization what it is….well except maybe the lightbulb (let’s give the Edison that one).

Yeah. spot on.. https://shaunynews.com/2016/02/24/how-scotland-invented-the-modern-world/

Many Scots migrated to the American South before the Civil War, and had large landholdings there as well as slaves.

Many Scotch-Irish migrated to America before the start of the American Revolutionary War, and a good many (particularly in the Carolinas) served with distinction in the Southern Campaign of that war (1780 – 82). The Battle of Kings Mountain, the turning point of the American Revolution in the South, was fought primarily by these Scotch-Irish and Ulster Scots on both sides.

Excellent article! The extraordinarily pugnacious character of the Scots was revealed in many Confederate Soldiers!

Many of the poor farm boys who fought the battles for the CSA were Scots-Irish. They died for the goals of a land and slave owning aristocracy, some of whom were Scots. Several of who fought were my ancestors and some died. This war was not simple. Good job.

I think you will find that all wars are largely fought by the poor and ultimately benefit the rich. The Southern soldier who fought in the War Between the States was not the only one who fought for the defense of their land and yet benefited the rich landowners and blockade runners who profited from the war. The Northern soldier – the farmboys from Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio and Indiana – were also fighting to invade the Southland in a war that benefited rich industrialists, railroad barons, and bankers with their blood. They were no different than the farmboys from the Carolinas, Alabama, Texas, Arkansas and Virginia who did the same. A generation later Rough Riders and Buffalo Soldiers would die going up San Juan Hill to benefit the owners of sugar plantations. God knows that Scotland and Ireland – and England for that matter – have a long and bloody history where this has been the case too.

You look at every war and ask yourself which king, landowner, businessman, ect did not profit at the expense of the poor who were sent off to the killing fields to pay with their blood.

There is a recording of the “Rebel Yell” that was made at a Civil War reunion.